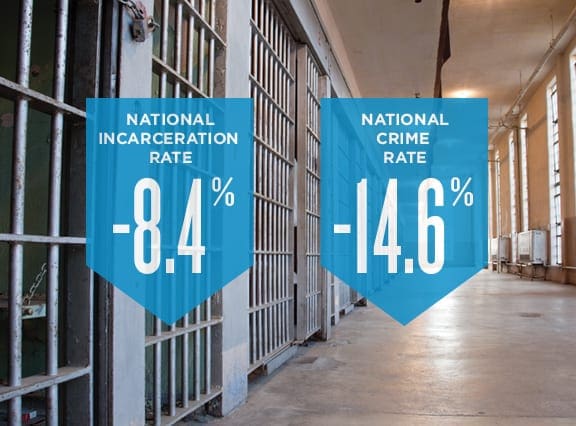

From 2010 to 2015, DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that the nation’s rate of incarceration fell 8.4 percent, while the combined rate of violent and property crime fell 14.6 percent.

Is it possible to reduce crime and imprisonment rates in the United States at the same time? Recent reports from the Department of Justice say the answer is yes.

According to the latest numbers from DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), the nation’s rate of incarceration fell 8.4 percent from 2010 to 2015, while the combined rate of violent and property crime fell 14.6 percent during the same period. An analysis of the new numbers by the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Public Safety Performance Project, which collaborates with the Public Welfare Foundation on criminal justice reform issues, shows that 31 states were able to cut both rates simultaneously.

Even with the new numbers, the U.S. still has the highest rate of incarceration in the world. In nearly half of the states that showed a reduction in the prison population, the decline was less than two percent.

And, as the Pew analysis pointed out, “The lack of a consistent relationship between the crime and imprisonment trends reinforces the findings of the National Research Council and others that the imprisonment rate in many states and the nation as a whole has long since passed the point of diminishing public safety returns.”

Whether looking at long- or short-term trends in crime rates, they still seem promising. For example, the latest survey of crime victims –the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) done by BJS last fall – showed that there was no statistically significant change in the rate of violent crime from 2014 to 2015. In fact, there was a slight decrease, from 20.1 victimizations per 1,000 people in 2014 compared to 18.6 victimizations per 1,000 people in 2015.

This differed somewhat from the latest Uniform Crime Report (UCR) from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which showed a decrease in the overall crime rate, despite a slight increase in violent crime. According to the FBI statistics, the violent crime rate increased by 3.9 percent in 2015 and homicides increased by 10.8 percent. This was the first increase in the violent crime rate in several years—and preliminary data from local law enforcement officials show that the spike in violent crime has continued in the first part of 2016. But overall, the number of murders was still less than in the 1980s and 1990s.

Unquestionably, even one additional homicide is too many and an uptick in the violent crime rate is not welcomed and should be addressed through crime prevention strategies that have been successful. Despite higher murder rates in 19 of the 30 largest cities, three cities in particular — Baltimore, MD, Washington, DC, and Chicago, IL — accounted for more than half of the national increase in murders. Experts at the Brennan Center for Justice, a Public Welfare Foundation grantee, suggested that what was going on was more reflective of local circumstances than a national trend.

Specifically, an analysis by the Center concluded that “community conditions,” such as decreasing populations, higher poverty rates, and higher unemployment than the national average, were major factors driving the murder rate increases in Baltimore, Washington and Chicago.

In an effort to put the new figures in historical perspective, outgoing Attorney General Loretta E. Lynch said the report, “also reminds us of the progress that we are making. It shows that in many communities, crime has remained stable or even decreased from the historic lows reported in 2014. And it is important to remember that while [violent] crime did increase over all last year, 2015 still represented the third-lowest year for violent crime in the past two decades.”

That is important to remember at a time when there is significant bipartisan interest in criminal justice reform to deal with the 2.2 million Americans who are incarcerated. The push to reform sentencing laws and other criminal justice policies is particularly relevant in the states, where more than 80 percent of the nation’s prisoners are held.

The Public Welfare Foundation supports several of these state efforts through its investment in state-based policy groups, as well as its support for national partners, such as the Alliance for Safety and Justice (ASJ), Right on Crime and Prison Fellowship. These and other groups are focusing on state sentencing reforms, like reducing mandatory minimum sentences, reclassifying some non-violent felonies as misdemeanors, and reforming probation and parole practices and policies.

Thus far, most of these changes have been aimed at nonviolent offenses, but to make meaningful progress in reducing state prison populations, addressing violent offenses will have to be part of the solution. That’s the conclusion of a recent report, Defining Violence: Reducing Incarceration by Rethinking America’s Approach to Violence, by grantee Justice Policy Institute (JPI).

“If we scrutinize all laws, policies, and practices that affect the length of time that someone is in prison and individually assess a person’s ability to change, we can reduce prison populations, and free up the resources to make bigger investments to reduce the harm caused by crime, and have safer communities,” said Marc Schindler, JPI’s executive director.

Crime survivors also broadly support reforming the criminal justice system to make rehabilitation more of a priority than punishment, and to reduce long sentences that do not protect public safety. In a first-of-its-kind survey of crime survivors, grantee ASJ found that six in ten victims preferred shorter prison sentences and more spending on prevention and treatment to long sentences and more spending on prisons and jails. Most importantly, these views cut across party lines and there is wide support for reform even among victims of violent crime.

As Aswad Thomas, national victims’ services coordinator for ASJ, put it, “The communities most harmed by crime and violence are the least supported by the criminal justice system. What these communities need is more investment in prevention, more investment in treatment, and more investment in community organizations that serve victims within the community.”

There is still a lot of work to be done to achieve these goals at the state and local levels, but these types of investments will reduce crime and incarceration even further and make all of our communities safer.